1Cal Poly Pomona; 2Virginia Tech

8 March 2011 – La Vela Latina Beach Bar, Playa Sámara, Guanacaste – Greetings from atop the Nicoya Peninsula seismogenic zone in Costa Rica! We write to you from our beachside table at a popular tavern on Playa Sámara, a fine spot to chill out after a productive day of gritty fieldwork beneath the sweltering Nicoya sun. We are here engaged in our second NSF MARGINS field expedition examining the neotectonics and paleoseismology of the northern Costa Rican fore arc. This project is funded by a collaborative grant entitled: “Seismogenesis of the Middle America Trench at the Nicoya Peninsula over multiple seismic cycles”. Jeff Marshall (Cal Poly Pomona) and his students are studying uplifted paleoshorelines to constrain spatially variable patterns of long-term deformation along the Nicoya coast. Jim Spotila (Virginia Tech) and his students are coring coastal estuaries in search of stratigraphic evidence for short-term seismic cycle displacements.

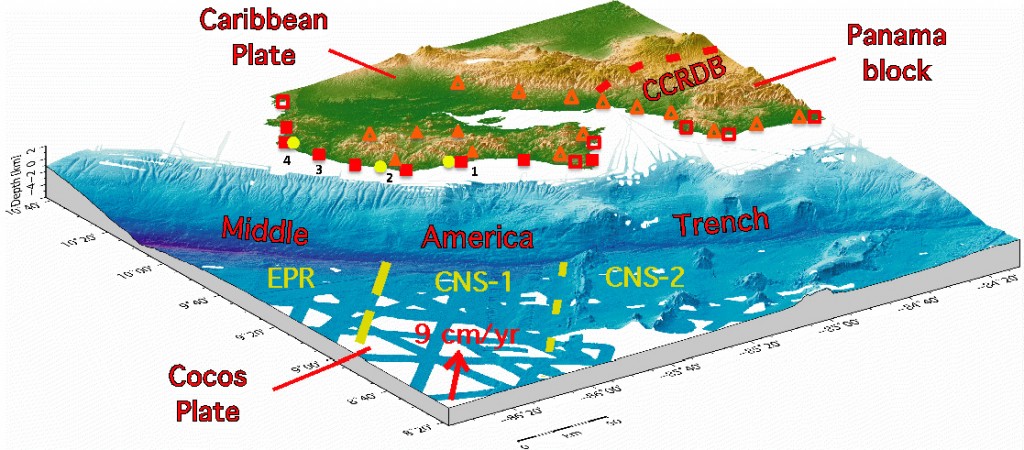

Figure 1. DEM of the northern Costa Rica convergent margin showing primary field sites for this NSF MARGINS project (solid symbols), and prior study sites from related projects (open symbols). Focus of research at each site indicated by symbol shape: marine terraces (squares), river terraces (triangles), and paleoseismic coring (circles). Numbers indicate sites discussed in this article: 1) Puerto Carrillo and Río Ora Valley; 2) Boca Nosara and Punta Peladas; 3) Playa Junquillal and Playa Negra; 4) Tamarindo Estuary. Variations in neotectonic deformation and seismogenesis along the Costa Rica margin are related to three contrasting domains of subducting seafloor offshore: EPR, CNS-1, and CNS-2. (DEM courtesy of C.J. Petersen, IFM-GEOMAR).

Our joint fieldwork this week focuses on the central Nicoya coast within the area of maximum uplift associated with the seismogenic zone. Our all-star crew includes field savvy grad students Shawn Morrish (Cal Poly Pomona) and Phil Prince (Virginia Tech), as well as geochronology guru Lewis Owen and his post-doc Madhav Murari (U. Cincinnati). Today, we split into two teams, one group seeking datable deposits on river terraces near the coast, and the other exploring coastal wetlands for new coring sites.

Figure 3. Virginia Tech students (from left Alyssa Durden, Keith DePew, and Craig Cunningham) during last year’s field expedition measuring paleoseismic sediment core extracted from mangrove tidal flat at Tamarindo Estuary.

The Terrace Team (Marshall, Morrish, Owen, and Murari) headed up the Río Ora Valley inland of Puerto Carrillo to collect samples for 10Be cosmogenic radionuclide dating of radiolarian chert boulders stranded on the surface of late Pleistocene river terraces. These huge bright red boulders are a distinctive feature of the local landscape. Eroded out of oceanic basement rocks in the nearby hills (Cretaceous Nicoya Complex), these boulders were transported downstream by the river and deposited along flood plain terraces. These terraces have undergone progressive uplift and now lie 40 meters above the modern incised channel of the Río Ora. Lewis assures me that the chert has strong potential for revealing the boulder ages, thus allowing us to determine rates of river incision and terrace uplift.

Figure 2. The “Terrace Team” sampling radiolarian chert boulders for 10Be exposure age dating of late Pleistocene river terrace, Río Ora Valley. Left to right: Madhav Murari (U. Cincinati), Shawn Morrish (Cal Poly Pomona) & Lewis Owen (U. Cincinati).

The shrill ping of our hammers chipping away at brutally hard chert inspired a few loud protests from Howler Monkeys congregated in trees just across the river. The commotion also caught the attention of a few large Brahma bulls in surrounding fields. Fortunately, they were more interested in cavorting with the cows than chasing us away. Our noisy pursuits also raised the curiosity of local residents in nearby ranch houses. One kind old “sabanero” who came out to investigate told us that the locals refer to these boulders as “Piedras de Fuego” or “Stones of Fire”. He said that the Chorotega people who once inhabited this valley believed the stones were a source of powerful mystic energy. At a minimum, we hope that they preserve a measurable signal from radionuclide decay.

While the Terrace Team sampled boulders, the Wetland Team (Spotila and Prince) scouted nearby estuaries for potential coring sites that might reveal records of seismic cycle displacements. Despite the impressive jaws of a 5-foot long crocodile patrolling the mouth of the Carrillo estuary, Jim and Phil donned their waders and bravely slogged out into the muddy mangrove swamp. At one site, they uncovered some intriguing peat horizons separating sharp contrasts in sediment grain size. Radiocarbon dating and facies analysis will hopefully reveal if these strata are earthquake related. Similar coring studies last year focused on the northern Nicoya Peninsula within an area of low net uplift (Tamarindo estuary). That work revealed sedimentation rates that are two slow to preserve adequate paleoseismic records. This year we are targeting wetlands along the central coast within areas of faster net uplift and presumably greater coseismic displacements. If the crocodiles permit, we hope to extract some useful data on past earthquakes.

11 March 2011 – Lagarta Lodge, Boca Nosara, Guanacaste – We gather around morning coffee, only to learn that a Magnitude 8.9 earthquake has ruptured the northern subduction zone of Japan, spawning a destructive tsunami. For a team of nerdy field geologists, armed with laptops, I-pads, and a sketchy wireless connection, this quickly devolves into a tap-and-click competition to access the best seismic data, tsunami models, and real-time disaster videos. We soon begin to appreciate the magnitude of this destructive event. From one subduction zone to another, our thoughts reach out to the people of Japan.

Figure 4. Shawn Morrish, Kelly Kinder, Andrew Barnhart (Cal Poly Pomona) sample basalt from marine terrace tread for 36Cl exposure age dating, Playa Negra.

The hotel owner tells us that the local emergency commission has issued a tsunami alert with waves from Japan expected to arrive on the Nicoya Peninsula in the late afternoon. Despite this warning, we head out for fieldwork along the coast. Jim and Phil descend into the Río Nosara wetlands for more paleoseismic coring, while Jeff, Shawn, Lewis, and Madhav hike out along the beach at Punta Peladas in search of terrace sampling sites. “Hmmm, interesting how empty the beach is today!” We are emboldened by the tsunami models we saw online, showing a 4:15 pm arrival of a relatively small wave. Oh, savor the irony, field geologists entrusting their lives to geophysicists! We can see the headlines now: “Six geologists swept out to sea. Geophysicists apologize for modeling error.” Yes indeed, this is interdisciplinary plate margins science in action!

At the appointed hour, we return to the “Sunset Bar” at our hotel, perched on the cliff top at Boca Nosara, 40 meters above the beach. This hotel is the officially designated disaster evacuation site for the local community. A crowd begins to gather, tourists and townspeople mingling and waiting with great anticipation to watch the spectacle. It’s “Tsunami Hour” here at the Sunset Bar in Nosara.

With digital cameras in hand, smart phones buzzing, and wireless laptops glowing with imagery, we read of tsunami impacts around the Pacific basin – Hawaii, California, and Mexico. Now breaking news from Nicaragua tells of ongoing evacuations along low-lying coastal areas. And, here at the Sunset Bar, the “turistas” jabber and clink bottles, “tica” moms chase after squawking kids, and “gringo” geologists speak in low authoritative tones of tsunami wavelengths, celerity, and run-up. Everyone watches the horizon.

Then, at 4:15 pm, the predicted time of wave arrival, nothing much happens. Well, yes, we think that maybe there was bit more movement in the water, wider wave crests perhaps, and the run-up, well, maybe it seemed a little higher. But, all in all, nothing remarkable happens. Sunset proceeds as normal toward the celebrated green flash, fisherman still work the river mouth as the tide rises, and the Sunset Bar gradually empties as people disperse for dinner. Apparently, at least for now, we dodged a bullet here on the other side of the pond. But, silently, all along the Nicoya coast, the ground ever-so-slowly continues to subside, the tides cut inland a bit further, and the peninsula accumulates a bit more strain energy, awaiting its turn to jump-up and shake.

16 March 2011 – Hotel Iguanazul, Playa Junquillal, Guanacaste – Greetings from another cliff top perch along the Nicoya Peninsula! The sun is setting as another excellent field day comes to an end. This time, we are at Playa Junquillal, up north where the cliffs are shorter and the first marine terrace lies at half its elevation at our prior locations. The Virginia Tech and Cincinnati groups have flown home to the US, and five more geology majors from Cal Poly Pomona have joined Jeff and Shawn for a second week of fieldwork focused on terrace mapping and sampling.The new members of Team Nicoya are Andrew Barnhart, Amber Butcher, Kelly Kinder, Brent Ritzinger, and Kacie Wellington. These undergraduate students are participants in the REU program supported by our MARGINS grant. Each student is working on a senior thesis focused on one of a series of field sites along the Nicoya coast. These individual projects each contribute a separate piece to the overall research puzzle. Our MARGINS supported fieldwork, both this year and last, builds upon several decades of prior neotectonics research on the Nicoya Peninsula. Together, these studies have documented significant variations in net Quaternary uplift along the Nicoya coastline. On a first order, these variations appear to be related to along-strike differences in the subducting seafloor and seismogenic zone observed by other MARGINS scientists.

Our fieldwork today, took us first to Playa Negra, a world-famous surfing beach featured in the classic cult film Endless Summer II. Our goal was to sample basalt outcrops along the cliff edge for 36Cl exposure age dating of the first marine terrace tread. As we plodded across the beach with field packs, rock hammers, and hiking boots, we generated some curiosity among surfers and sunbathers. “Hey, are you guys like scientists or something?” “Totally, dude.”

Having learned the drill yesterday, the students performed like a well-oiled machine, chipping out samples, labeling sample bags, taking notes, measuring cliff heights, and recording GPS coordinates. And, most importantly, they carried all the samples and gear! It’s nice to be in charge.

Leaving Playa Negra, we drove inland on rocky ranch roads to a wooded area on the second marine terrace where we had seen more of the red chert boulders. Again, the students jumped into action, sampling five of the Stones of Fire with stunning efficiency. If only I can get them to write up their research reports with such blinding speed! I think it was helpful to entice them with an incentive of cool beverages and lunch in the shade at a favorite eatery up the road. As we left the field with our samples in hand, we stumbled upon a remarkable 7-foot long snakeskin stretched across on the ground. We were quite glad we discovered this only as we were leaving the field! I’m sure the beast that left the skin is not far away.

A popular Chortega legend here on the Nicoya Peninsula tells of a giant trembling serpent that lives deep inside the mountains. When provoked, this angry creature links its tail with a similar monster beneath Laguna de Apoyo in Nicaragua, and the two serpents thrash about causing violent shaking of the earth. During the colonial era, Spanish priests began leading an annual pilgrimage to a prominent Nicoya hilltop to plant crosses and calm the angry serpent. This practice continues to this day, with a yearly ritual held each 3rd of May on the summit of Cerro las Cruces. Despite the good intentions of such an earthquake mitigation strategy, large temblors still rock the Nicoya Peninsula several times each century.

Figure 5. MARGINS REU “Team Nicoya” at crater of Volcán Póas. Left to right: Jeff Marshall (P.I.), Andrew Barnhart, Amber Butcher, Kelly Kinder, Shawn Morrish, Brent Ritzinger, Kacie Wellington (Photos by Jeff Marshall).

The last major rupture of the Nicoya seismogenic zone (M 7.7) struck the peninsula on 5 October 1950. This event killed and injured dozens of people, severely damaged buildings and roads, and produced landslides, liquefaction, and abrupt coseismic coastal uplift. Beach residents and fishermen describe a sudden retreat of the ocean that exposed submerged headlands and broad areas of the rocky intertidal platform. During subsequent decades, the tides slowly reclaimed this area and waves now reach further inland than before the 1950 earthquake. High tides routinely inundate parts of the coastline, washing over roads, undermining trees, and sweeping into beachside homes and tourist hangouts. Such changes are apparent all along the central Nicoya coast as the shoreline gradually subsides and strain builds toward the next earthquake. Despite the impending hazard, this beautiful region has become an epicenter for rapid coastal development driven by Costa Rica’s world-renowned tourism trade. Construction of hotels, condominiums, and vacation homes proceeds without heed for the lurking earthquake hazard. It is critical therefore, that geoscientists, government officials, and local residents develop a better understanding of the megathrust earthquake cycle beneath the Nicoya Peninsula. Through our research, we hope to contribute to this understanding by defining patterns of both short-term seismic cycle motions, as well as long-term net deformation along the Nicoya seismogenic zone.

To learn more, visit: http://serc.carleton.edu/vignettes/collection/25559.html

Marshall, J., Morrish, S., Butcher, A., Ritzinger, B., Wellington, K., LaFromboise, E., Protti, M., Gardner, T., and Spotila, J., 2010, Morphotectonic segmentation along the Nicoya Peninsula seismic gap, Costa Rica: Eos, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union, v. 91, Abs. T11D-2138.

Spotila, J.A., Kennedy, L.M., Durden, A., Depew, K., Smithka, I., Cunningham, C., Marshall, J.S., Prince, P.S., and Tranel, L.M., 2010, Paleoseismic investigations of the Middle America Trench on the Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica: A feasibility study of the Tamarindo estuary: Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs, v. 42, no. 5, Abs. 250-3.

Acknowledgements

Our research is conducted in collaboration with Marino Protti and Victor González (OVSICORI-UNA, Costa Rica) and many other fine colleagues working on NSF MARGINS science along the Nicoya Peninsula.

GeoPRISMS Newsletter, Issue No. 26, Spring 2011. Retrieved from http://geoprisms.nineplanetsllc.com